The trajectory of human well-being is a fundamental concern for anthropology, archaeology, and sociology. Understanding how societies have evolved in terms of longevity offers a profound lens through which to view historical, social, economic, and environmental changes. This article delves into the historical evolution of life expectancy in Latin America from the dawn of the 20th century to the present day, examining the factors that have shaped this crucial demographic indicator and exploring its implications for the region's future.

Table of Contents

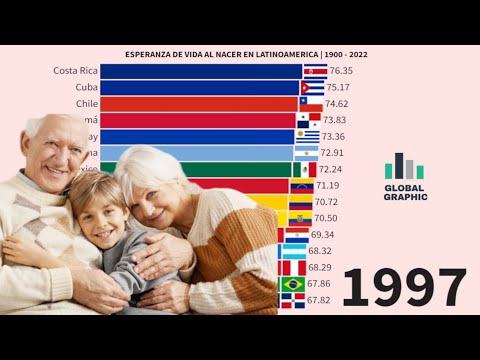

Introduction: Decoding Longevity in Latin America

Life expectancy, a statistical measure of the average time an organism is expected to live, is a powerful proxy for a society's health, living conditions, and overall development. In Latin America, a region characterized by immense diversity in its peoples, cultures, and socio-economic landscapes, the story of life expectancy is a complex tapestry woven with threads of progress, disparity, and resilience. This exploration aims to provide a comprehensive overview, drawing upon historical data and anthropological insights, to illuminate the journey of Latin American populations towards longer, healthier lives.

The Early 20th Century: A Precarious Beginning

At the turn of the 20th century, life expectancy across Latin America was considerably low, often hovering in the range of 30 to 40 years. This was a reality mirrored in much of the developing world at the time. The primary drivers of this low longevity were:

- High rates of infectious diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, cholera, smallpox).

- Inadequate sanitation and access to clean water.

- Limited healthcare infrastructure and medical knowledge.

- High infant and child mortality rates.

- Periods of political instability and conflict.

- Subsistence-level agriculture and precarious living conditions for a significant portion of the population.

During this period, anthropological studies would have revealed stark differences in living conditions based on social class, ethnicity, and geographical location. Indigenous communities, often marginalized, frequently faced even more challenging circumstances. The data from sources like Clio Infra provides a critical baseline for understanding the profound transformations that were yet to come.

"The early 20th century was a period where survival, rather than longevity, was the primary human concern for vast segments of Latin American society."

Mid-Century Advancements and Shifting Trends

The mid-20th century marked a significant turning point. Following World War II and with increasing global focus on public health, several factors began to contribute to a notable increase in life expectancy throughout Latin America:

- Public Health Initiatives: Widespread vaccination campaigns drastically reduced mortality from diseases like polio and measles.

- Improved Sanitation and Water Systems: Investments in infrastructure led to better access to clean water and sewage disposal, curbing waterborne illnesses.

- Advances in Medicine: The development and wider availability of antibiotics and other medical treatments played a crucial role.

- Nutritional Improvements: Better agricultural practices and food distribution systems helped combat widespread malnutrition.

The United Nations (ONU) and the World Bank became key sources for demographic data from this era onwards, allowing for more systematic tracking of these trends. Anthropologists observing these changes would have noted the societal shifts accompanying increased longevity, including changing family structures and evolving concepts of old age.

Late 20th and Early 21st Century: Progress and Persistent Challenges

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, most Latin American countries had achieved significant gains in life expectancy, with many surpassing 70 years. This period, however, also highlighted the persistent inequalities within the region. While overall life spans increased, disparities remained based on:

- Socioeconomic Status: Wealthier populations consistently enjoyed longer lives due to better access to healthcare, nutrition, and healthier living environments.

- Urban vs. Rural Divide: Rural areas often lagged behind urban centers in terms of healthcare access and infrastructure.

- Ethnic and Racial Disparities: Indigenous and Afro-descendant populations frequently faced systemic disadvantages contributing to lower life expectancies.

- Healthcare System Quality: The effectiveness and accessibility of national healthcare systems varied greatly across countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s also presented a stark reminder of the fragility of these gains, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations and temporarily impacting life expectancy trends in several nations. Understanding these dynamics requires a nuanced look at the cultural and social structures that influence health outcomes.

"The statistical improvements in life expectancy mask deeply entrenched social and economic inequalities that continue to shape the lived experiences of Latin Americans."

Key Influencing Factors

Several overarching factors have shaped the trajectory of life expectancy in Latin America:

- Economic Development: Overall economic growth has often correlated with improved living standards and health outcomes, though the distribution of this wealth is critical.

- Political Stability: Periods of peace and stable governance have allowed for sustained investment in public health and infrastructure. Conversely, conflict and instability have had detrimental effects.

- Technological Advancements: Medical breakthroughs, diagnostic tools, and treatment options have continuously improved care.

- Education Levels: Higher education, particularly for women, is strongly linked to better health choices and outcomes for individuals and their families.

- Globalization and International Cooperation: Global health organizations and cross-border initiatives have played a role in disseminating best practices and resources.

- Environmental Factors: Climate change, pollution, and natural disasters pose increasing threats to health and longevity.

The interplay of these factors highlights the need for interdisciplinary approaches, integrating insights from anthropology, sociology, history, and psychology to fully grasp the complexity of human well-being.

DIY: Analyzing Demographic Data

Understanding demographic trends like life expectancy can be approached through a practical, DIY lens. By utilizing publicly available data, one can begin to explore these patterns independently. Here’s a simplified guide to analyzing life expectancy data:

- Identify Reliable Data Sources: Begin by locating reputable sources for life expectancy data. International organizations like the World Bank, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) are excellent starting points. National statistical institutes (e.g., INEGI in Mexico, IBGE in Brazil) also provide valuable country-specific information.

- Define Your Scope: Decide which countries or sub-regions within Latin America you wish to study. Consider the time period you are interested in. For instance, you might focus on a specific decade or compare two distinct periods.

- Gather the Data: Download or copy the life expectancy figures for your chosen scope. Data is often presented in tables or spreadsheets. Pay attention to whether the data represents overall life expectancy, or if it's broken down by sex (male/female).

- Visualize the Data: Use simple tools like spreadsheet software (e.g., Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets) to create charts and graphs. A line graph is ideal for showing trends over time. Bar charts can be effective for comparing life expectancies across different countries at a specific point in time.

-

Interpret the Trends: Analyze the visual representations. Look for:

- Overall upward or downward trends.

- Periods of significant change or stagnation.

- Comparisons between different countries or demographic groups.

- Seek Contextual Information: While data provides the "what," historical and anthropological research provides the "why." Research major events (e.g., introduction of vaccines, significant economic reforms, major health crises) that occurred during the periods of change you observe. This contextualization is crucial for a deeper understanding. For example, consult historical documents or academic articles on public health policies in the region.

This hands-on approach allows for a personalized exploration of demographic history and its underlying social, economic, and political influences.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the current average life expectancy in Latin America?

- As of recent estimates (circa 2020-2022), the average life expectancy across Latin America hovers around 73-75 years. However, this average masks significant variations between countries and within them.

- Which Latin American country historically had the highest life expectancy?

- Historically, countries like Costa Rica and Uruguay have often shown higher life expectancies, often attributed to robust social welfare systems and accessible healthcare. However, this can fluctuate based on specific data years and metrics.

- How did infectious diseases impact early 20th-century life expectancy?

- Infectious diseases were the leading causes of death, particularly among infants and children. Diseases like tuberculosis, smallpox, and diarrheal diseases significantly reduced average lifespans before widespread vaccination and sanitation improvements.

- Are there significant differences in life expectancy between men and women in Latin America?

- Yes, generally, women in Latin America tend to have a higher life expectancy than men, a trend observed globally. This is often attributed to a combination of biological factors and differences in lifestyle, risk-taking behaviors, and healthcare-seeking patterns.

Conclusion: Towards a Healthier Future

The journey of life expectancy in Latin America from 1900 to 2022 is a testament to human progress, driven by scientific advancements, public health initiatives, and socio-economic development. The dramatic increase from precarious early-century figures to contemporary levels reflects transformative changes in living conditions and healthcare. However, this narrative is incomplete without acknowledging the persistent disparities that continue to affect millions across the region. As we look to the future, addressing these inequalities through inclusive policies, strengthened healthcare systems, and sustainable development will be paramount in ensuring that the benefits of increased longevity are shared by all inhabitants of this vibrant and diverse continent.

We invite you to share your thoughts and insights in the comments section below. Your perspectives enrich our understanding of these complex human stories.