Hello and welcome to El Antroposofista, your gateway to the fascinating realms of anthropology, archaeology, psychology, and history. This article delves into the core branches of anthropology, seeking to understand the multifaceted nature of human existence across time and cultures. Our intention is to provide a rigorous yet accessible overview, catering to the academic curiosity of those seeking a deeper comprehension of humanity's past and present. We will not only explore the theoretical underpinnings of these fields but also offer practical insights into how anthropological concepts can be applied in real-world scenarios.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Anthropological Imperative

- Cultural Anthropology: Understanding Societies and Meanings

- Archaeological Anthropology: Unearthing the Past

- Biological Anthropology: The Human Biological Story

- Linguistic Anthropology: Language as a Cultural Key

- Applied Anthropology: Bridging Theory and Practice

- DIY Practical Guide: Conducting Basic Ethnographic Observations

- Frequently Asked Questions

Introduction: The Anthropological Imperative

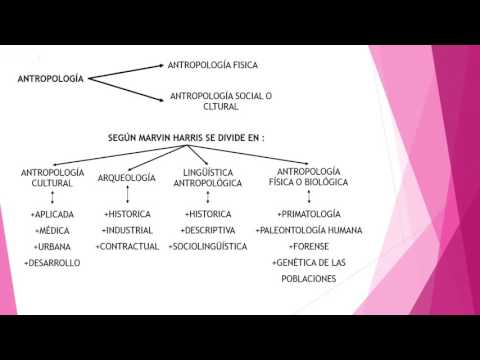

Anthropology, as a discipline, grapples with the fundamental question of what it means to be human. It is a holistic science, striving to understand the complete human experience, past and present. The discipline is broadly divided into several interconnected branches, each offering a unique lens through which to examine our species. From the intricate social structures of contemporary societies to the fossilized remains of our ancient ancestors, anthropology seeks to paint a comprehensive picture of human diversity and commonality. This exploration is not merely an academic exercise; it is an imperative for fostering cross-cultural understanding and navigating an increasingly complex globalized world. As the field of sociology often intersects with anthropology, understanding the theoretical frameworks proposed by scholars like Pierre Bourdieu becomes crucial in analyzing social stratification and cultural capital within various societies.

Cultural Anthropology: Understanding Societies and Meanings

Cultural anthropology is perhaps the most widely recognized branch. It focuses on the study of human societies and cultures, their development, and the relationship between people and their cultures. Cultural anthropologists often employ ethnographic methods, living within communities to gain an insider's perspective on their customs, beliefs, social structures, and daily lives. They explore kinship systems, economic practices, political organizations, and religious beliefs, aiming to understand the diversity of human cultural expression. Key concepts include ethnocentrism (viewing one's own culture as superior) and cultural relativism (understanding beliefs and practices within their own cultural context). The study of indigenous cultures, for instance, reveals profound insights into human adaptation and resilience.

The goal of anthropology is to understand the totality of human existence, past and present, and to communicate this understanding to others.

This branch is crucial for understanding phenomena like Mexican immigration or the complexities of cultural identity in diverse populations. It helps us appreciate the vast array of human adaptations and the subjective meanings people ascribe to their world.

Archaeological Anthropology: Unearthing the Past

Archaeology, while often considered a distinct field, is fundamentally a branch of anthropology. It seeks to understand human history through the excavation and analysis of material remains. Archaeologists study artifacts, structures, biofacts (like bones), and cultural landscapes left behind by past societies. This allows them to reconstruct past ways of life, social organization, technologies, and environmental interactions, even for cultures that left no written records. From the earliest stone tools to the ruins of ancient cities, archaeological findings provide tangible evidence of human ingenuity and evolution. The meticulous work of archaeological methods allows us to trace the development of human societies over millennia, offering a crucial counterpoint to written historical accounts.

Consider the study of ancient civilizations in Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence sheds light on their complex calendars, agricultural practices, and societal structures, often complementing or even correcting earlier historical interpretations.

Biological Anthropology: The Human Biological Story

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, examines the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates. This branch explores human evolution, genetic variation, biological plasticity, and the biological influences on behavior. Biological anthropologists study fossil hominins to trace our evolutionary lineage, analyze primate behavior to understand our origins, and examine human variation in contemporary populations to understand adaptation to diverse environments. Topics include primatology, paleoanthropology, and human genetics. The study of hominid evolution is central to this branch, providing insights into our species' journey from early hominids to modern humans. Understanding the biological underpinnings of human behavior is also crucial for fields like psychology.

Human biological diversity is not a sign of inferiority or superiority, but rather a testament to our species' remarkable capacity for adaptation.

This branch is essential for understanding our shared biological heritage and the evolutionary forces that have shaped us. It also informs discussions around topics like gender and human biology, moving beyond simplistic biological determinism.

Linguistic Anthropology: Language as a Cultural Key

Linguistic anthropology is the study of language in relation to social and cultural life. It investigates how language shapes social identity, cultural beliefs, and cognitive processes. Linguists explore the structure of languages (phonetics, syntax, semantics), their historical development, and their social and cultural contexts. This includes studying dialectal variation, language change, language acquisition, and the relationship between language and power. The focus is not just on grammar but on how language is used in real social interactions. Understanding linguistic heritage is key to preserving cultural diversity. The study of voseo in Latin America, for example, reveals fascinating insights into regional identity and linguistic evolution.

This field is critical for understanding cross-cultural communication and the role language plays in shaping perceptions of reality, including understanding different Latin American cultures and their unique linguistic expressions.

Applied Anthropology: Bridging Theory and Practice

Applied anthropology utilizes anthropological theories, methods, and data to address contemporary social problems. Applied anthropologists work in a variety of settings, including international development, public health, education, business, and government. They might help design culturally appropriate health interventions, assist in community development projects, or conduct market research informed by cultural understanding. This branch emphasizes the practical relevance of anthropological knowledge in solving real-world challenges and improving human well-being. The insights gained from studying migrant populations are often crucial in the work of applied anthropologists focused on human rights and integration.

The application of anthropological knowledge is vital in areas such as immigration policy, socioeconomic development, and conflict resolution, demonstrating the discipline's direct impact on society.

DIY Practical Guide: Conducting Basic Ethnographic Observations

This guide provides a simplified framework for conducting ethnographic observations, a core method in anthropology. It's designed for anyone interested in understanding social dynamics in their immediate environment.

- Define Your Focus: Before you begin, identify a specific phenomenon, group, or location you wish to observe. For example, "interactions in a local café" or "pedestrian behavior at a busy intersection."

- Choose Your Setting and Time: Select a suitable location and time that aligns with your research question. Consider when the behavior you are interested in is most likely to occur.

- Be an Observer: Position yourself where you can see and hear clearly without drawing undue attention. Aim to be unobtrusive. Minimize your own interactions initially.

- Take Detailed Notes: Use a notebook or a digital device to record your observations. Be as descriptive as possible. Note down:

- Who is present?

- What are they doing?

- What are they saying (if audible)?

- What is the physical environment like?

- What are the interactions like between individuals?

- Your own initial thoughts and interpretations (clearly marked as such).

- Record Observations Systematically: Try to observe for a set period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) and take notes continuously. If possible, conduct multiple observation sessions at different times or days to capture variability.

- Reflect and Analyze: After your observation session, review your notes. Look for patterns, recurring behaviors, themes, and anomalies. What do your observations suggest about the social dynamics or behaviors you were studying? How do they relate to broader anthropological concepts?

- Consider Ethical Implications: Be mindful of privacy. Avoid recording identifiable information about individuals without their consent. If your observations are about public spaces, be aware of local norms and ethical guidelines.

This practical exercise, even on a small scale, offers a taste of the observational skills crucial to anthropological fieldwork and understanding human behavior in its natural context. It relates to the broader concept of understanding cultures through direct engagement.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the four main branches of anthropology?

The four main branches are cultural anthropology, archaeological anthropology, biological (or physical) anthropology, and linguistic anthropology.

What is the primary goal of cultural anthropology?

The primary goal is to understand the diversity of human societies and cultures, their beliefs, practices, and social structures, often through ethnographic fieldwork.

How does archaeology contribute to anthropology?

Archaeology provides empirical evidence of past human behavior and societal development through the study of material remains, helping to reconstruct history and understand long-term human trends.

What is the role of language in linguistic anthropology?

Linguistic anthropology studies language as a fundamental aspect of human culture, examining how it shapes thought, social identity, and interaction, and how it evolves over time.

Can anthropological knowledge be applied to solve real-world problems?

Yes, applied anthropology specifically focuses on using anthropological theories and methods to address contemporary social issues in areas like public health, development, and policy.

El Antroposofista invites you to continue exploring these fascinating disciplines. We believe that a deeper understanding of anthropology is crucial for navigating our shared human journey. Visit our official blog for the latest news and analyses in anthropology, archaeology, psychology, and history. If you appreciate our work, consider supporting us by exploring our store for unique NFTs, offering a contemporary avenue for collaboration and engagement with our content.