Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Silk Road's Enduring Legacy

- The Genesis and Evolution of the Silk Road

- Mechanics of Exchange: Beyond Mere Commerce

- Goods and Innovations in Transit

- Challenges and Risks of the Journey

- Cultural and Intellectual Crossroads

- The Enduring Legacy of the Silk Road

- DIY Practical Guide: Tracing Your Own Trade Routes

- Frequently Asked Questions

Introduction: The Silk Road's Enduring Legacy

The Silk Road conjures images of vast caravans traversing arid deserts and treacherous mountain passes, laden with exotic goods. Yet, the reality of this ancient network was far more complex and profound than simple commerce. It was a dynamic artery of human connection, facilitating not only the exchange of tangible commodities but also the transmission of ideas, technologies, and cultures across continents. This article delves into the intricate workings of the Silk Road, exploring its historical context, the mechanics of its operation, the diverse array of goods and knowledge exchanged, and its lasting impact on the world we inhabit today.

The Genesis and Evolution of the Silk Road

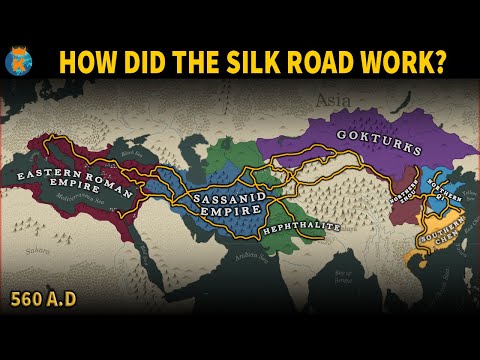

The concept of the Silk Road as a singular, unified highway is largely a modern construct. In reality, it was a sprawling network of routes that evolved organically over centuries, primarily flourishing between the 2nd century BCE and the 15th century CE. Its origins can be traced to the Han Dynasty's westward expansion in China, seeking alliances and trade opportunities. The initial impetus was often strategic: the desire for reliable access to resources, particularly the famed Chinese silk, which was highly coveted in the West, especially within the Roman Empire.

Early Chinese expeditions, such as that of Zhang Qian in the 2nd century BCE, aimed to establish diplomatic ties and gather intelligence on potential trading partners. These early forays laid the groundwork for more extensive commercial activities. Over time, the network expanded, connecting East Asia with Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, and eventually reaching the Mediterranean world and Europe. This vast web of routes was not static; it shifted and adapted in response to political changes, the rise and fall of empires, and the emergence of new technologies.

"The Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road" by Luce Boulnois (2004) highlights how diverse groups, from religious pilgrims to military escorts, contributed to the functioning and protection of these trade routes.

Mechanics of Exchange: Beyond Mere Commerce

The operation of the Silk Road was a multifaceted endeavor, far removed from the streamlined global trade we know today. It was a decentralized system characterized by a series of intermediaries and regional markets. Goods rarely traveled the entire length of the network in a single transaction. Instead, they passed through multiple hands, with local merchants and caravan leaders specializing in specific segments of the journey.

Caravans, often composed of hundreds of camels, were the primary mode of transport across land routes. These journeys were arduous, time-consuming, and fraught with danger. Oasis towns and established trading posts served as vital hubs for rest, resupply, and exchange. Cities like Samarkand, Bukhara, and Dunhuang flourished as cosmopolitan centers where goods and cultures converged.

The economic principles at play were complex. Prices fluctuated significantly based on distance, risk, and demand. Silk, for instance, commanded exorbitant prices in Rome due to the numerous intermediaries and the perilous journey it undertook. The value was not just in the commodity itself but in the arduous process of its transportation and the exclusivity it represented.

Maritime routes, often referred to as the "Maritime Silk Road," also played a crucial role, particularly for bulkier goods and during periods when land routes were unstable. These sea lanes connected ports in Southeast Asia, India, the Persian Gulf, and East Africa, complementing the overland networks and further integrating distant economies.

Goods and Innovations in Transit

While silk was the namesake commodity, the Silk Road facilitated the exchange of an astonishing variety of goods. From East to West flowed not only silk but also spices, porcelain, tea, paper, gunpowder, and precious stones. These items transformed economies and daily life in distant lands.

The westward flow of goods also fueled innovation. The secret of papermaking eventually reached the Islamic world and then Europe, revolutionizing record-keeping and the dissemination of knowledge. Gunpowder, initially used for fireworks in China, found its way to the West, fundamentally altering warfare.

Conversely, goods flowed from West to East. Horses, glassware, gold, silver, wool, linen textiles, and agricultural products like grapes and alfalfa moved eastward. These introductions enriched the economies and diets of Central Asian and Chinese populations.

As John E. Hill notes in "Through the Jade Gate to Rome," the later Han Dynasty period saw intensified trade, with goods like Roman glassware appearing in Chinese archaeological sites, illustrating the direct or indirect connections.

Beyond material goods, the Silk Road was a conduit for intangible exchanges. Religious ideas, philosophical concepts, artistic styles, and scientific knowledge traversed these routes. Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia and East Asia, transforming religious landscapes. Nestorian Christianity and later Islam also found adherents along the network.

Challenges and Risks of the Journey

Undertaking a journey along the Silk Road was a testament to human endurance and courage. Merchants and travelers faced a multitude of challenges:

- Harsh Environments: Vast deserts like the Taklamakan, towering mountain ranges such as the Pamirs, and extreme weather conditions posed constant threats.

- Banditry: Routes were often patrolled by raiders, and protecting caravans required significant security measures, including armed escorts.

- Disease: Close proximity in caravans and the movement of people and animals facilitated the spread of epidemics, which could decimate trading parties.

- Political Instability: The rise and fall of empires and local conflicts could disrupt trade routes, making travel perilous or impossible.

- Logistical Hurdles: Arranging supplies, finding reliable guides, and navigating unfamiliar territories demanded considerable planning and resourcefulness.

These risks significantly contributed to the high value placed on goods transported along the Silk Road. The perilous nature of the journey was as much a part of the product's cost as the labor involved in its creation.

Cultural and Intellectual Crossroads

Perhaps the most profound impact of the Silk Road was its role as a catalyst for cultural diffusion and intellectual exchange. The constant movement of people – merchants, pilgrims, soldiers, diplomats, and artisans – led to an unprecedented blending of traditions and perspectives.

Artistic motifs traveled and transformed. Gandharan Buddhist art, for example, shows a clear Hellenistic influence, a direct result of interactions facilitated by the Silk Road following Alexander the Great's campaigns. Musical instruments, artistic techniques, and architectural styles were shared and adapted across cultures.

The exchange was not merely one-way; it was a dynamic dialogue between civilizations, fostering innovation and cross-cultural understanding.

Scientific and technological knowledge also flowed freely. Advances in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and cartography were shared. The development of paper, printing techniques, and the compass, originating in China, eventually made their way westward, profoundly influencing the course of global history. The Silk Road was, in essence, an early form of globalization, knitting together disparate societies into a loosely connected network.

The Enduring Legacy of the Silk Road

Though the overland Silk Road declined with the rise of maritime trade and political shifts, its legacy continues to resonate. It stands as a powerful historical precedent for global interconnectedness and the transformative power of exchange. Modern initiatives, such as China's "Belt and Road Initiative," explicitly draw inspiration from the historical Silk Road, aiming to revive and expand infrastructure and trade links across Eurasia.

Studying the Silk Road offers invaluable insights into history, anthropology, and economics. It reminds us that human progress has often been driven by interaction, cooperation, and the willingness to explore beyond familiar horizons. The mechanics of its operation, from caravan logistics to the valuation of exotic goods, provide a fascinating case study in pre-modern global trade and the resilience of human enterprise.

DIY Practical Guide: Tracing Your Own Trade Routes

Understanding the Silk Road's reach can be made more tangible by imagining and tracing historical trade routes, even on a smaller scale. This exercise helps appreciate the logistical challenges and the interconnectedness of different regions.

- Choose a Region and Era: Select a historical period and a specific geographical area that interests you. This could be the Roman Empire, Han Dynasty China, or a medieval European trade network. For this exercise, let's focus on a hypothetical segment of the Silk Road.

- Identify Key Hubs: Research significant cities, oases, or ports within your chosen region and era that served as important trading centers. For example, if focusing on the Central Asian segment, consider cities like Merv, Bukhara, or Kashgar.

- Map a Hypothetical Route: Using historical maps or online mapping tools, sketch out a plausible trade route connecting these hubs. Consider geographical features like rivers, mountains, and deserts that would have influenced travel.

- Select Goods for Exchange: Decide what goods would plausibly travel along this route. For instance, between Eastern Central Asia and the Middle East, you might imagine silk, jade, and spices moving westward, while horses, glassware, and textiles move eastward.

- Consider the Intermediaries: Think about who would have transported these goods. It's unlikely one merchant traveled the entire route. Identify potential intermediary points where goods might change hands. Local caravan leaders, oasis traders, and port merchants would be key players.

- Estimate Time and Challenges: Research the approximate travel times between key points during that era. Consider the potential challenges: weather, terrain, security risks (bandits, political unrest), and the need for resupply. This helps understand why goods were so valuable.

- Visualize the Exchange: Imagine the interactions at a trading hub. What languages might be spoken? What cultures would converge? What innovations might be shared? This step brings the human element of trade to life.

- Document Your Findings: Create a simple report, map, or presentation detailing your hypothetical trade route, the goods exchanged, the challenges faced, and the cultural interactions. This process provides a hands-on understanding of the Silk Road's mechanics.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Was the Silk Road a single road?

A1: No, the Silk Road was not a single, paved road but rather a complex network of overland and maritime routes that evolved over centuries, connecting different regions at various times.

Q2: What was the most important good traded on the Silk Road?

A2: While silk gave the route its name and was highly prized, a vast array of goods, including spices, precious metals, textiles, paper, and innovations, were traded. The exchange of ideas and religions was also profoundly significant.

Q3: Who traveled the Silk Road?

A3: Travelers included merchants, monks, pilgrims, soldiers, artisans, diplomats, and explorers from diverse cultures and empires across Eurasia.

Q4: How long did it take to travel the Silk Road?

A4: Travel times varied immensely depending on the route segment, mode of transport, season, and prevailing political conditions. Journeys could take months or even years to complete.

Q5: Did the Silk Road only involve trade?

A5: No, beyond commerce, the Silk Road was a crucial conduit for the transmission of religions (like Buddhism and Islam), philosophies, technologies (such as papermaking and gunpowder), artistic styles, and scientific knowledge, fostering significant cultural diffusion.

Sources:

- Boulnois, Luce. (2004). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE.

- Documentary on the Silk Road